If you thought Scott’s final expedition was gripping, consider Ernest Shackleton‘s 1914-1916 voyage on the Endurance. Shackleton was a colleague of Scott’s and had accompanied him in his first trip to Antarctica. Shackleton himself had mounted a 1908-1909 expedition to the South Pole, but was forced to turn back just 97 miles shy. After Amundsen and Scott reached the South Pole in 1912, Shackleton seems to have grown antsy with the desire to find some other “first” to accomplish. He decided that he would attempt an overland crossing of the entire Antarctic continent, by way of the South Pole. It would constitute a distance of 1800 miles. When he announced the expedition, he received 5,000 applications for ~50 positions! The ad read:

MEN WANTED for hazardous journey, small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful, honor and recognition in case of success.

The Endurance sailed south, aiming to land at Weddell Bay. But before they could reach the shore, the ship was trapped in pack ice. As winter, and darkness, descended on the crew, they realized they would be stuck in the ice for months, until summer could break up the ice and set them free. So they sat there, wedged in the ice, huddled against the tremendous cold and perpetual darkness. To relieve boredom, they played hockey and football out on the ice. The ship lasted a phenomenal 10 months in this state until finally it succumbed to the pressure of the ice on either side and was crushed. This image, by Shackleton’s photographer, Frank Hurley, shows the end, with the sled dogs in the foreground as though at a funeral. The crew was left stranded on the ice. The Heart of the Great Alone includes many of Hurley’s dramatic and beautiful photographs, well worth browsing.

The Endurance sailed south, aiming to land at Weddell Bay. But before they could reach the shore, the ship was trapped in pack ice. As winter, and darkness, descended on the crew, they realized they would be stuck in the ice for months, until summer could break up the ice and set them free. So they sat there, wedged in the ice, huddled against the tremendous cold and perpetual darkness. To relieve boredom, they played hockey and football out on the ice. The ship lasted a phenomenal 10 months in this state until finally it succumbed to the pressure of the ice on either side and was crushed. This image, by Shackleton’s photographer, Frank Hurley, shows the end, with the sled dogs in the foreground as though at a funeral. The crew was left stranded on the ice. The Heart of the Great Alone includes many of Hurley’s dramatic and beautiful photographs, well worth browsing.

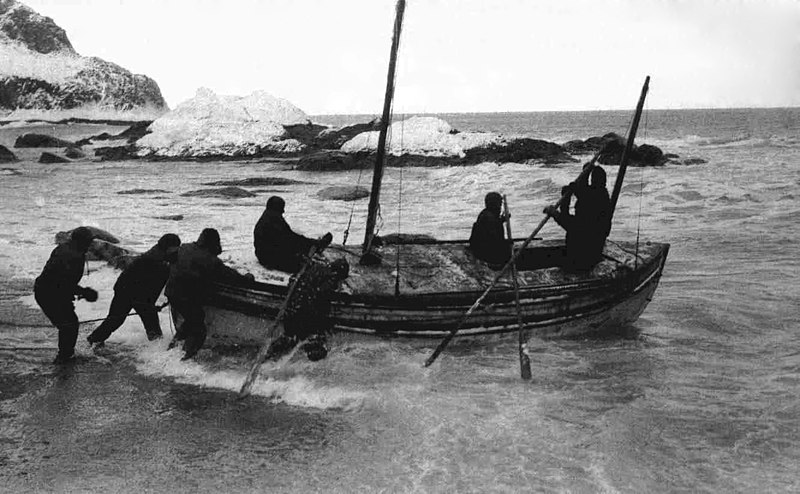

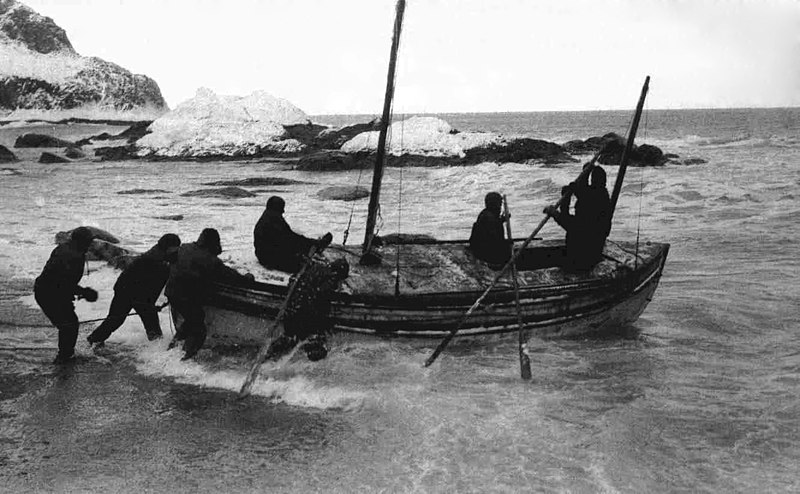

The ship, however, had not been stationary despite being stuck. Instead, it had drifted with the ice, traveling over 1100 miles north and west, away from Shackleton’s original goal, but closer to the possibility of rescue. Shackleton knew of a hut with food and stores in it, on Paulet Island, 346 miles away. They had three lifeboats, but they couldn’t sail to the island, because there was no open water. Two months later, the ice was weakening beneath them, so he and his 27 men set off across the ice, dragging their lifeboats and stores with them. They ended up camped on an ice floe. Four months later, they finally were able to launch the lifeboats into open water. They landed on a different island, Elephant Island, which had no stores for them to reach. Shackleton decided to set off with 5 men in one of the lifeboats, aiming for South Georgia, in hopes of persuading a whaling boat to return and pick up the rest of his men.

South Georgia was 800 miles (!) away, across one of the stormiest seas in the world at that time of year. Shackleton and his men managed to cross it in an open lifeboat, over 16 days of storms, cold, and thirst. Unfortunately, when they finally landed on South Georgia, they were on the wrong side of the island. So Shackleton and two of his men climbed over the island’s mountains and glaciers (a feat no one had yet achieved), with no sleeping bags or tent, through a day, a night, and the following day. On May 16, they reached the whaling station and, the next day, headed back in a whaling ship. They picked up the other three men on the far side of the island and headed south, but were turned back by pack ice. Two more failed attempts were made until finally, on August 30, 1916, Shackleton was reunited with his men on Elephant Island.

South Georgia was 800 miles (!) away, across one of the stormiest seas in the world at that time of year. Shackleton and his men managed to cross it in an open lifeboat, over 16 days of storms, cold, and thirst. Unfortunately, when they finally landed on South Georgia, they were on the wrong side of the island. So Shackleton and two of his men climbed over the island’s mountains and glaciers (a feat no one had yet achieved), with no sleeping bags or tent, through a day, a night, and the following day. On May 16, they reached the whaling station and, the next day, headed back in a whaling ship. They picked up the other three men on the far side of the island and headed south, but were turned back by pack ice. Two more failed attempts were made until finally, on August 30, 1916, Shackleton was reunited with his men on Elephant Island.

This story is just incredible. And the most incredible thing is that, in all that time, and through all that hardship, not one man was lost. (Frostbitten toes were, however.)

Check out this map of Shackleton’s voyage (beginning and ending in South Georgia), and marvel at this amazing accomplishment:

When Shackleton finally returned to England, any celebration of his achievement was muted by the fact that England was embroiled in World War I, and thousands of men were dying by the day. The great yawning brutal abyss of Antarctica, and its shivery challenges, and the heroic battles Shackleton and his men waged to stay alive, all were dwarfed by the horrors that humans back home managed to inflict upon each other.

So far I have contributed observations of a praying mantis (needs review) and a raccoon (research grade!). When you log an observation and connect it with a species, you also get to see a map of where else that species has been seen.

So far I have contributed observations of a praying mantis (needs review) and a raccoon (research grade!). When you log an observation and connect it with a species, you also get to see a map of where else that species has been seen.