February 16th, 2013 at 3:22 pm (Education, Library School, Psychology)

The Library Science program I’m in (at San Jose State Univ.) has a career guidance site that includes a recommendation to take the Eureka self-assessment to learn more about your “interests, skills, and personality characteristics.” Like all such instruments, it can only tell you what you already know at some level, but who doesn’t enjoy being categorized by a quiz?

Here is what I learned from Eureka about myself:

- Personality: “You are a natural leader.”

- Learning style: Logical/independent.

- Most important values: Education, independence, integrity, accomplishment, and health.

- Least important values: Money/wealth, recognition, security, family, and belonging.

The first one made me reflect for a little while. I don’t think of myself as a leader, and certainly not a “natural” one (“natural” to me implies something that comes with ease). If anything, I’m a reluctant leader. And yet there’s something that drives me to step in when leading (or organizing) needs doing. Maybe that’s what they meant. If only I had more charisma and less cynicism, I could go into politics :)

Their longer description of this characterization did resonate with me:

“You respect competence and intellectual abilities both in yourself and in others. You may want to understand and control the realities of life, and are on the lookout for new projects, new activities and new procedures. You are usually the driving force behind any organization or activity in which you participate.”

Also:

“You tend to lose interest once the work is no longer challenging.”

The second statement is that I am a logical/independent learner. Their text includes this gem: “If you are a logical learner, you may like using your brain for logical and mathematical reasoning.” I enjoyed this characterization:

You may use phrases like these:

- That’s logical.

- Let’s make a list.

- Follow the process, procedures or rules.

- We can work it out.

- There’s no pattern to this.

- Prove it!

Those are all very familiar!

Another great quote: “Out of order issues, materials or people may cause you stress.”

The summary of my values pretty much nails them, except that I’d place family higher. (The questions about family all were phrased as family you live with, which I don’t.)

The site also encourages you to discuss these results with those who know you to gain additional perspective. If you agree/disagree with these items, feel free to comment!

2 Comments

2 of 2 people learned something from this entry.

September 29th, 2012 at 11:07 pm (Books, Psychology)

Woe, Twitter, IM-speak, dumbing down of young brains.

You’ve heard it before, but you probably haven’t heard it like this. Dr. Maryanne Wolf writes about what we’ve learned about the neurobiology of reading, what the brain is doing during the process of learning to read and the act of reading itself. In Our ‘Deep Reading’ Brain: Its Digital Evolution Poses Questions, she shares her worries about how today’s digital push for faster, skimmier reading encourages us to disable our ability to read deeply, reflect, and go beyond what’s in the text.

You’ve heard it before, but you probably haven’t heard it like this. Dr. Maryanne Wolf writes about what we’ve learned about the neurobiology of reading, what the brain is doing during the process of learning to read and the act of reading itself. In Our ‘Deep Reading’ Brain: Its Digital Evolution Poses Questions, she shares her worries about how today’s digital push for faster, skimmier reading encourages us to disable our ability to read deeply, reflect, and go beyond what’s in the text.

“We need to understand the value of what we may be losing when we skim text so rapidly that we skip the precious milliseconds of deep reading processes. For it is within these moments—and these processes in our brains—that we might reach our own important insights and breakthroughs.”

We all do this. I bet you skimmed part of this article, which is itself a condensation of her article (which I encourage you to read in full!). But hey, after two or three paragraphs, we’re getting it, we’re agreeing, we want to move on, encounter something new! Right?

“We need to find the ability to pause and pull back from what seems to be developing into an incessant need to fill every millisecond with new information.”

Amen to that. Smartphones are the killer information device. I never need fear downtime or long waits at the doctor’s office again. I have Slashdot and blogs and Kindle books galore. But now I find in any waiting time, no matter how short, I itch to pull out my phone. Unlock the thing and snack at the information buffet, cruising through Slashdot blurbs in search of the one or two items about which I actually want to read more details. What am I doing?!

Asked whether Internet reading might aid speed reading, Dr. Wolf replied, “Yes, but speed and its counterpart—assumed efficiency—are not always desirable for deep thought.”

I think that is one of the reasons I continue to post to this blog. There is a part of me that believes that being forced to slow down and write about what I’ve encountered (often, by reading) will help me to think a bit deeper on what it all means.

What do you think? Did you read this far?

4 Comments

2 of 3 people learned something from this entry.

August 23rd, 2012 at 10:03 pm (Books, Psychology)

The online Fantasy & Sci-Fi class has moved on from the darkly gothic horror of Dracula to the psycho-drama of Frankenstein. Here’s what I chose to write about. Peer reviews are very welcome. ;)

Victor Frankenstein: Friend to None

The desire for friendship drives the plot of “Frankenstein,” and the story is a tragedy not just because of Victor’s transgressions and poor moral choices, but because he never learns how to be a true friend.

Friendship is presented as an essential ingredient for a virtuous life. The monster states, “My vices are the children of a forced solitude that I abhor; and my virtues will necessarily arise when I live in communion with an equal.” Walton, who is likewise eager for friendship, opines that “such a friend [would] repair [his] faults.” Yet Frankenstein, who is blessed with friendship and support from all around him, does not improve from their influence, because he does not perceive its value. His own words reveal him to be an unrelentingly self-focused individual, obsessed with his own goals, desires, and pains.

The monster hungers for a friend whom he imagines “sympathizing with my feelings and cheering my gloom.” He is devastated when the de Lacey family rejects him. His hopes are raised when Victor agrees to create a female companion, then dashed when Victor destroys her. The monster responds by killing Clerval, Victor’s closest friend. Victor is enraged by this loss, yet he does not see the analogy to what he has done to the monster.

Most pointedly, Victor’s lack of regard for friendship aggravates the central conflict. An obvious solution presents itself: if he could not create a companion for the monster, he could have been that companion himself. It is clear that showing the least crumb of sympathy or affection for his creation would have radically altered the monster’s catastrophic course. Yet Victor never considers this route. Despite the major examples in his life (his father’s support, Elizabeth’s affections, Clerval’s dedication), he never learns to offer those things to another—and that is what makes “Frankenstein” a tragedy.

Comments

August 19th, 2012 at 8:12 am (Psychology)

As someone subject to perfectionist tendencies, I enjoyed reading this article on Excellence vs. Perfection. The former is defined by its focus on process, while the latter focuses on results.

While the article highlights perfectionism’s negative impact on self-esteem, I couldn’t help also noticing that the excellence-focused path just seemed a lot less stressful.

“The pursuer of excellence sets realistic but challenging goals that are clear and specific whereas the perfectionist set unreasonable demands or expectations.”

This goes beyond just setting realistic goals for a single task — but also to time management and prioritization: how many tasks can you realistically accept? If you are constantly striving to do or complete more than you realistically can, and unsatisfied until they are all done “properly”, are you setting yourself up for unremitting stress and, ultimately, burnout?

“The pursuer of excellence would examine the situation and make decisions about what is most important to do, where they can set limits by saying “no,” and when they can delegate.”

An excellence-seeker can accept criticism and suggestions, since they aid in the process of improvement. A perfectionist instead sees them as challenges or reminders that they have not reached their goal.

The article also encourages us to slow down and to be patient in our pursuit of excellence.

“The pursuer of excellence finds enjoyment and satisfaction in the pursuit of goals whereas the perfectionist is usually unhappy or dissatisfied. When goals or risks are challenging and achievable and are not attached to the self-concept they can be fun to pursue.”

Overall, this was a welcome perspective. I’m already predisposed to value the process of learning or acquiring skills over the end result. (So far this has worked quite well with my violin practicing, possibly because I’m not aiming for any kind of recital or skill level but instead simply to improve over time.) But it’s easy to get sidetracked by evaluations and grades in a school setting, or deliverables and publications at work. Here then is a nice reminder!

2 Comments

2 of 2 people learned something from this entry.

July 29th, 2012 at 6:04 pm (History, Psychology, Society)

One of my duties at the Monrovia Library is to take old newspapers on microfilm and scan them into electronic files. We anticipate this making them much easier for patrons to use, and it will mean less wear on the microfilm itself.

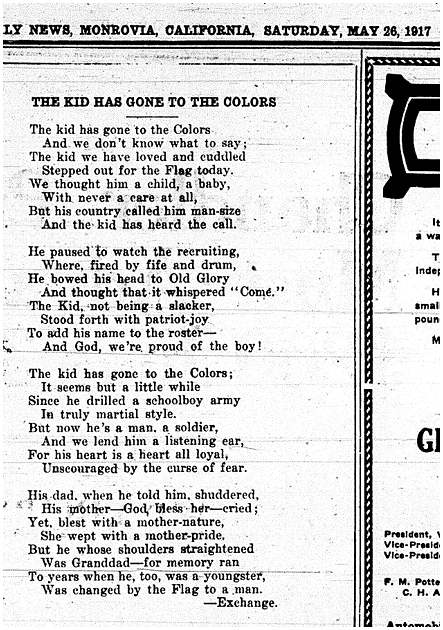

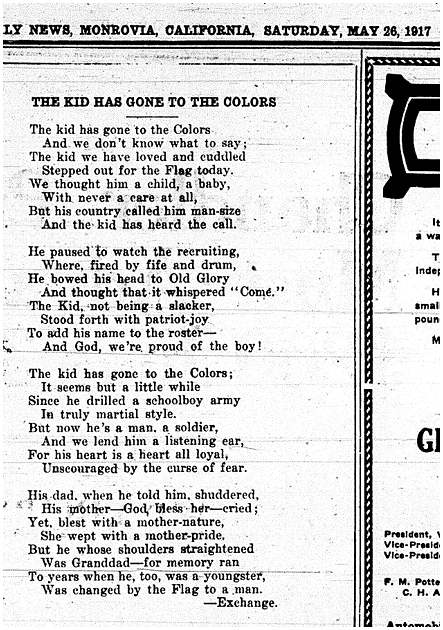

I’ve been working on scanning the Monrovia Weekly News from 1915-1917 lately, and sometimes my attention is caught by unusual ads or articles. This item, from May 26, 1917, definitely stood out.

For context, what was happening in 1917? That’s right, World War I (at the time, the Great War). The U.S. had declared war on Germany just seven weeks earlier, on April 6, 1917. Before it was over, we’d lose 116,000 U.S. lives.

And the straight-shouldered grandfather? He’d have possibly fought in the Civil War, 56 years earlier. A bit more complicated, that, to consider it an answer to the call of the Flag (presumably the North and nationalism, vs. the South and federalism).

Regardless, a sobering take on conscription and enlistment. Does our Flag have the same call today?

1 Comments

0 of 1 people learned something from this entry.