Do you have the dexterity needed to play the violin?

February 26th, 2013 at 10:09 pm (Biology, Music)

Three plastic surgeons decided to conduct a study of finger dexterity in violin and viola players versus the general population. The paper describing their findings, which was published in The Journal of Hand Surgery, has a title that tickles my funny bone:

Assessment of the presence of independent flexor digitorum superficialis function in the small fingers of professional string players: Is this an example of natural selection?, by Godwin, Wheble, and Feig.

The paper is, lamentably, behind a paywall, and I am unconvinced by the abstract that it is worth $32.00. But never fear, The Atlantic Monthly has provided a summary and analysis of the paper in an article titled Study: Violinists’ Fates Resides in Their Left Pinky Fingers.

The gist of their argument is that you can conduct tests to determine how much independent motion a person has for their pinky and their ring finger. Go ahead, test yourself:

Hold down the index, middle, and ring fingers of your left hand, then try to bend your pinky. Now try it again, but allow your ring finger to bend as well.

About 18 percent of people can do neither, according to a study in The Journal of Hand Surgery. But in a similar group of 90 professional musicians from “three of London’s leading orchestras” (38 first violinists, 33 second violinists, 19 viola players), none lacked this ability, and all but two were able to bend just their pinky finger.

(Source: Atlantic Monthly).

I can easily bend the ring and pinky fingers together, but I have only limited curl of the pinky on its own. Does this explain why I continue to struggle to get good intonation with 4th-finger stops?

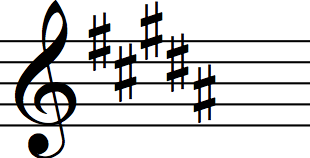

Picture from http://www.the-violin.com/violin-fingering-E.html

Apparently, Godwin et al. recommend testing children for this ability prior to signing them up for violin lessons. As a filter? Really?

As a possibly-slightly-impaired player, I’m more in favor of the Atlantic’s take: “[Instead,] music teachers could use this knowledge to go easy on kids who aren’t predisposed to the violin, instead of just telling them to practice more.”

Not so any more! I asked my teacher if I could learn some fiddle technique, since she also plays fiddle music. She immediately recommended “the only fiddle book you’ll ever need,” which turned out to be “The Craig Duncan Master Fiddle Solo Collection.”

Not so any more! I asked my teacher if I could learn some fiddle technique, since she also plays fiddle music. She immediately recommended “the only fiddle book you’ll ever need,” which turned out to be “The Craig Duncan Master Fiddle Solo Collection.”

For me, the struggle was in (as dumb as this sounds) using the whole bow. I’d gotten used to practicing with a small mid-section of the bow, as this made “enough” sound for me.

For me, the struggle was in (as dumb as this sounds) using the whole bow. I’d gotten used to practicing with a small mid-section of the bow, as this made “enough” sound for me.