The mysterious Goodyear blimp

November 27th, 2018 at 10:17 pm (Engineering, History)

On a recent drive across the desert from California to Arizona, I decided to stop and see the Blythe airport. I had flown over it, but never landed and visited. To my delight, as I rolled up in my car, I discovered that the Goodyear blimp had just landed!

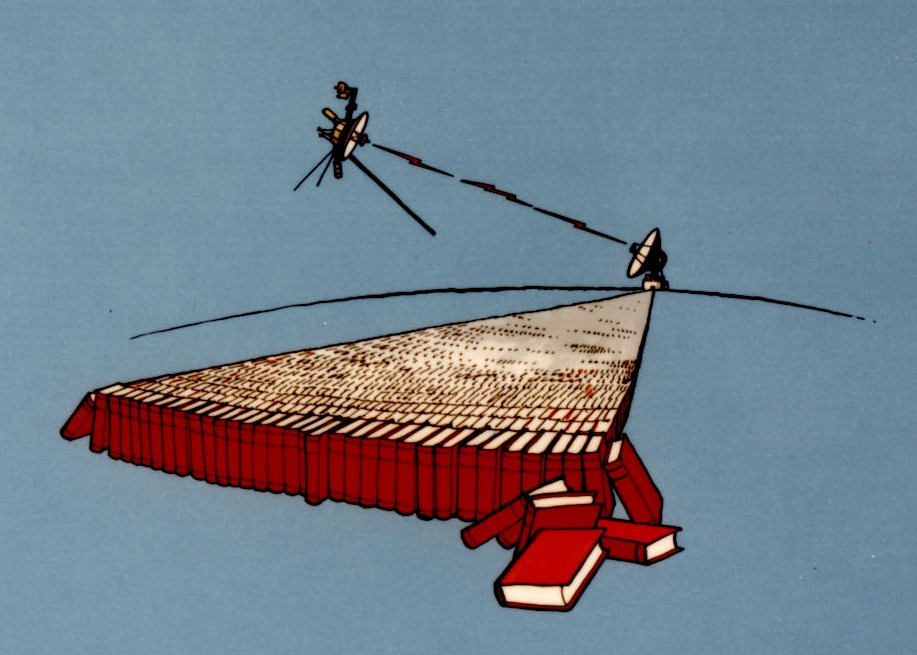

I had never seen it that close before. This one is Wingfoot Two (I later discovered that there are three in the current fleet). I talked briefly with one of the ground support staff and learned that the blimp was stopping in Blythe overnight on its way to Vegas to attend (and record/broadcast) a golf match. In this picture, the blimp is attached to a mobile mast on the right, and a tiny wheel at its aft end is touching the ground as they maneuver the blimp to its desired position. (Click the image to enlarge)

Later when I was back at a computer, I wanted to find out more about these blimps and how they work. Apparently Goodyear got into the lighter-than-air business in 1898, and in 1925 they flew the first blimp that used helium. Mostly they seem to have been used for advertising, and not just for their own tires. Some blimps have lighted panels on their sides where they can spell words or scroll messages; in 1966 they added the “Skytacular” which was in 4 colors and had animations; now they have “Eaglevision” which uses high-res LEDs and can show video :). I’ve never seen one in operation scrolling messages!

In WWII, they were used for patrolling the ocean (escorting navy convoys). I don’t know if they had any weapons.

In 1955, the blimp became the “first aerial platform to provide a live TV picture”… for the Rose Parade! :)

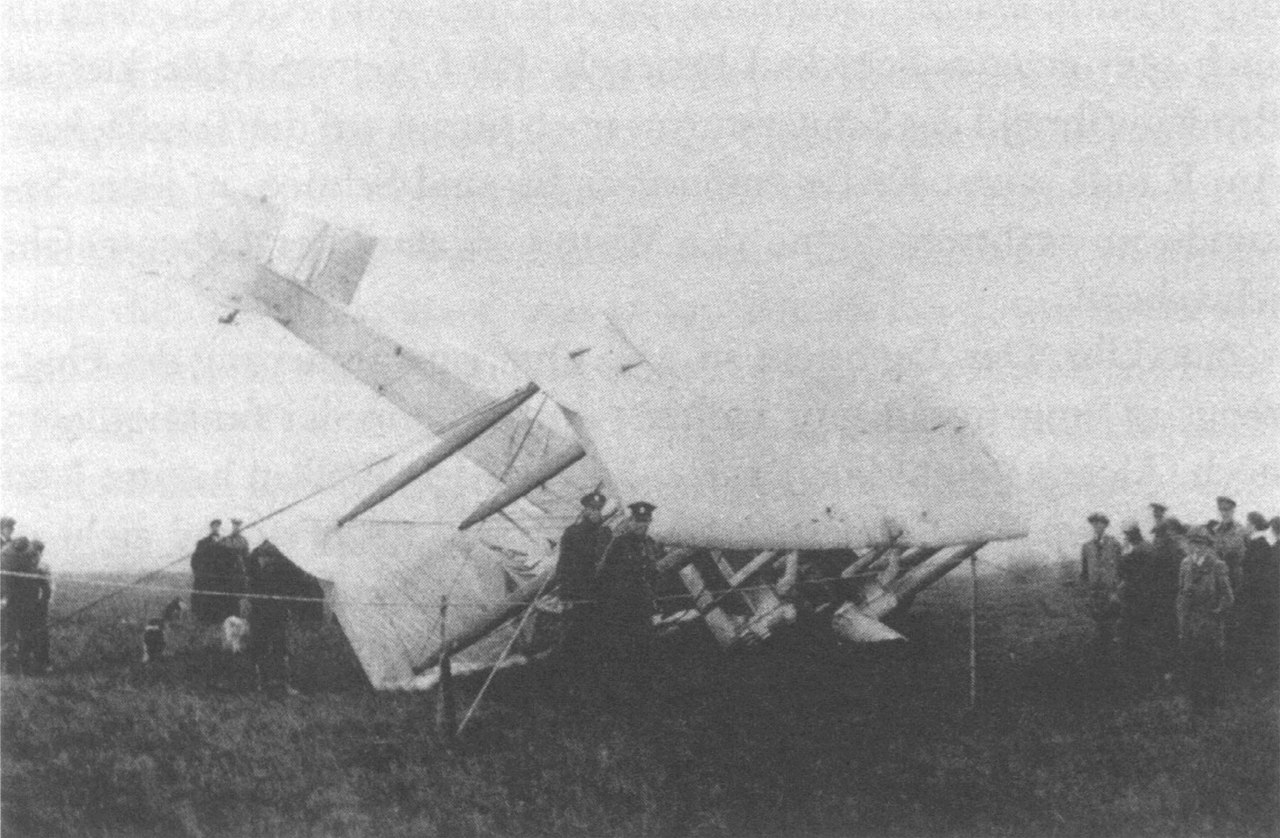

The Goodyear blimps use helium, which has about the same lifting force as hydrogen, but with the added benefit of not being explosive. The infamous Hindenburg disaster occurred when the (German) Hindenburg, which was also designed for use with helium, was instead filled with hydrogen, apparently because the U.S. was monopolizing helium for its own use, and helium had become correspondingly expensive internationally. The Hindenburg had 97 people onboard when it ignited in 1937 (36 died).

We actually have stunning real footage of the Hindenburg coming in to land and blowing up (!).

What Goodyear flies now is not technically a blimp (!) (“blimp” = no rigid structure) but instead a “semi-rigid airship” or “zeppelin”. (The Hindenburg was a third type of airship: fully rigid). However, Goodyear still encourages the use of the term “blimp.” Its max speed is 73 mph (not bad!), and it seats up to 14 people. Today’s Goodyear blimps are 246 feet long, compared with 804 feet (!) for the Hindenburg.

On my way back to California a few days later, I saw the blimp AGAIN, this time cruising eastward and following Interstate 10. It was less than 1000′ above the ground, which seemed curious to me. Fare you well, semi-rigid airship! :)

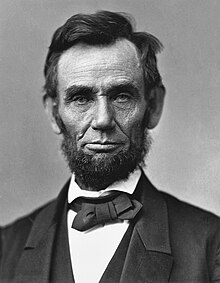

And finally, Prof. Gallagher noted in passing that President Abraham Lincoln appointed no less than

And finally, Prof. Gallagher noted in passing that President Abraham Lincoln appointed no less than