How much baking powder to use

April 24th, 2009 at 9:10 pm (Cooking, Food)

I posted previously about a dramatic biscuit failure I experienced when I forgot to include baking powder, due to a careless reading of the recipe. Instead of regular flour, it called for “self-rising flour”, which already has baking powder mixed in. The strange thing is, no one seems to agree on exactly how much baking powder should go into self-rising flour. Casual googling turned up recommendations for 0.5 tsp, 1 tsp, 1.25 tsp, and 1.5 tsp (same as 0.5 Tbsp) as the amount of baking powder to add for each 1 cup of flour.

Now the difference between 0.5 and 1.5 tsp may not sound like a lot, but consider that it represents a 50% increase or decrease from a middle value of 1.0 tsp. For something as sensitive to stoichiometry as baking is, I’d expect that to make a difference. Then again, it seems reasonable that the desired amount would vary depending on the item being baked and how much loft you hope to get — which sort of defeats the purpose of a pre-mixed flour-baking powder product.

But even specialized biscuit recipes disagree on this, but seem to choose either 1 tsp or 0.5 Tbsp (1.5 tsp, in agreement with my mom’s recipe). (As a side note, they also vary widely on how much shortening or butter to use, as well as how much milk or buttermilk to use and whether or not to chill the dry ingredients + butter. The number of permutations sent me into a brief paralysis (gosh darn it, shouldn’t we have converged on a solution by now?!) until I decided to give up on the web and just use my mom’s recipe.)

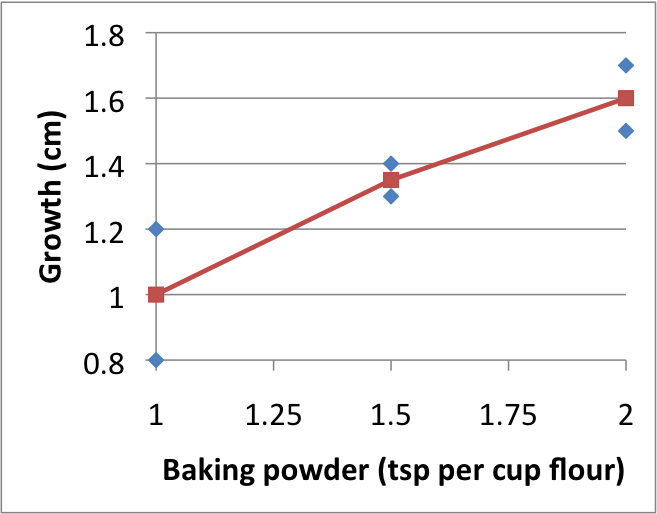

I decided that a scientific test was called for. I split up the flour involved in a batch of biscuits (2 cups) into three bowls, for baking powder:flour ratios of 1 tsp:1 cup, 1.5 tsp:1 cup, and 2 tsp:1 cup. There was enough material to make two full biscuits of each type, plus some extra left over for a partial-biscuit. I measured the biscuit height before and after baking. The following chart shows the average (across two biscuits) difference in height I observed (data points in blue, average in red).

A clear difference emerged! It’s even almost linear, which is a bit surprising given the small sample size. Now it would be interesting to try even smaller and larger amounts of baking powder… the curve is likely to have an interesting shape at both ends. But for food, one of the most important measures of success is not size, but taste. I sampled all of the results and found that I couldn’t really tell a difference between the 1.5- and 2-tsp results, but the 1-tsp biscuits were noticeably less fluffy. I conclude that the wise biscuit baker should avoid self-rising flour with less than 1.5 tsp of baking powder per cup of flour (or avoid it altogether and just add your own ingredients).

Some other notes:

- One of the annoyingly tedious parts of making biscuits or scones is the “cutting in” step that gets the fat (butter or shortening or whatnot) into the flour. I used a tip from my friend Evan: freeze the butter, then use a cheese grater to shred it into the flour. Mix with fingers. Works like a charm!

- Some biscuit recipes call for milk, some for milk with lemon juice added, and some for buttermilk. Ever wondered why? Well, adding lemon juice or using buttermilk lowers the pH of the liquid (makes it more acidic). And chemical leaveners such as baking powder and baking soda are basic, therefore in theory should react more strongly in an acidic environment (giving your baked good more “rise”). But baking powder is baking soda pre-combined with its own acid (cream of tartar). So you shouldn’t actually need an acidic liquid. I tested this by dropping some baking powder in water, then in buttermilk. If anything, the baking powder reacted more to the water than the buttermilk. (I should do the same test with baking soda.) This also explains (maybe) why some recipes use baking powder and others use baking soda + cream of tartar — the latter want control over the ratio, just like the self-rising-flour issue!

- Biscuit aficionados recommend the use of flour with a lower protein content (to get even more loft) such as cake flour; see How to make the best Buttermilk Biscuits from Scratch. I haven’t tried this one yet, either.

- I actually did a parallel experiment, with the same three types of mixtures, but first chilling the dry ingredients + butter. However, a distraction at a critical moment caused me to forget to measure the biscuits before they went into the oven! So I only have their post-baking heights. If anything, the relationship seemed weaker, with less rising action. While a firm conclusion should await more reliable data, for now I’m going on the assumption that the chilling step is unnecessary. (Taste is unaffected, too ;) )

Clearly, the field of interesting experiments with ingredient combinations is a rich and open one, even just for making biscuits!