Learning through playtime

February 19th, 2014 at 8:48 pm (Books, Education, Library School)

When are you most engaged and inspired to learn something new? Thomas and Brown, in their book “A New Culture of Learning,” argue that play is a powerful setting, and motivator, and facilitator for learning. Sitting down to a new board game, exploring an online MMORPG, experimenting to find the best baseball swing — these are all settings that push you to integrate new information and also to explore the limits of what’s possible. What happens if I click there?

When are you most engaged and inspired to learn something new? Thomas and Brown, in their book “A New Culture of Learning,” argue that play is a powerful setting, and motivator, and facilitator for learning. Sitting down to a new board game, exploring an online MMORPG, experimenting to find the best baseball swing — these are all settings that push you to integrate new information and also to explore the limits of what’s possible. What happens if I click there?

These are also settings that seem incompatible with the form that our public education currently takes.

Thomas and Brown sing the praises of the “new culture of learning,” which they define as unlimited access to information (i.e., the Internet) combined with an environment that allows for “unlimited agency to build and explore within boundaries.” Agency enables exploration and discovery, and the boundaries serve as spurs to imagination. Similarly, constrained art forms like the sonnet or haiku can provide boundaries that inspire new creations. Thomas and Brown also use the word “culture” deliberately, and not in the sense that probably first came to mind: think bacterial culture in a petri dish, something that grows through cultivation.

And in Chapter 2, something more radical emerges.

“For most of the twentieth century our educational system has been built on the assumption that teaching is necessary for learning to occur,” Thomas and Brown assert.

Wow. Yes! If a teacher is absent from the classroom, we assume that learning grinds to a halt, and that it is only through the teacher’s intervention that the students will learn anything. Yet a moment’s consideration raises a multitude of counter-examples. Have you ever read a wikipedia article out of curiosity? Watched a Youtube video to learn how to make mitered borders on a quilt? Tinkered with Legos to see how tall a tower you can build? Tried a new route to work to determine whether it’s a shorter commute? Invented a variation on a recipe? Read this blog to Learn Something New?

We are learning all the time, with or without teachers.

Thomas and Brown characterize our current view of learning as “mechanistic” in that “learning is treated as a series of steps to be mastered” in which “the goal is to learn as much as you can, as fast as you can.” That doesn’t sound so bad. In fact, the idea of an organized curriculum, a progression of easy to hard, sounds quite attractive to me. But it rests on some unstated assumptions that just might not be valid:

- That all knowledge *can* be organized in a logical series of steps. Is this true of every field?

- That the same organization of knowledge works equally well for everyone.

- That knowledge doesn’t change much over time. (Otherwise the curriculum would be in constant need of revision.)

Thomas and Brown discuss #3 in their book. The first two are mine, and I think both assumptions are suspect.

What can we do instead?

Thomas and Brown suggest viewing learning in terms of an “environment” (the boundaries mentioned before). The learning culture emerges from the environment in which people operate, and they learn through engagement in that world (not by being externally instructed). Learners are not constantly required to prove that they “get it” but can instead embrace what they don’t know and keep asking questions and exploring.

I am reminded of the critique of education levied by Sir Ken Robinson in 2010, brilliantly illustrated by RSA Animate (“Changing Education Paradigms”):

It gets especially relevant around 6:30 when he discusses the historical evolution of our approach to public education and how influenced it has been by the industrial revolution. What was most striking to me was the point about how we educate children in “batches” by age. Really, does this ever make any sense?

Moving to an emphasis on the environment and play opens up entirely new approaches to learning. It also places more responsibility on the learner: to be active, to explore, to prioritize his or her own learning. This is a natural outcome to reach as an adult, free of the pressures of obligatory schooling — yet so often we are consumed with life maintenance that we do not carve out time for learning or for play.

Thomas and Brown suggested that this is, or at least has been, a natural shift in priorities. They argue that historically, as children grew up, the world seemed more stable with age. People figured out how the world worked, and then could settle into a mostly static view of the world and the best strategies for interacting with it. But they argue that today, the amount of change (driven by technological advances) renders this strategy less successful.

It’s certainly not new to claim that today’s citizens experience a higher rate of change than those in the past. However, this is the first time I’ve seen a prescription for coping that encourages, effectively, more play. “Embrace change,” Thomas and Brown advocate. Open your arms, and your mind, to a rich environment that provides endless chances for learning and growth.

I will quibble slightly with one of their claims. I don’t think it’s uniquely the Internet that makes this kind of endless learning possible. Some people manufacture a learning environment wherever they go, constantly wondering “how does that work?” and “why does it look that way?” and “could I make one myself?” It’s all already there, anytime you want it.

Play on!

James Paul Gee, a professor of Reading, decided to explore the world of video games. He picked up a copy of

James Paul Gee, a professor of Reading, decided to explore the world of video games. He picked up a copy of

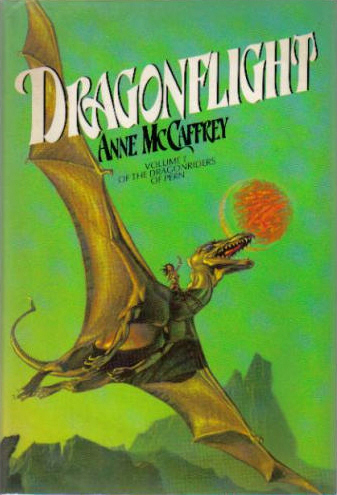

I was quickly captivated by the Pern-based games in which you could create a character who had the chance to be chosen as a dragonrider — every

I was quickly captivated by the Pern-based games in which you could create a character who had the chance to be chosen as a dragonrider — every