March 12th, 2025 at 9:59 pm (Technology)

So you have a flat tire and want to try out Fix-a-Flat, a spray can that claims to seal and re-inflate your tire for temporary use until it can be repaired. Your first and biggest challenge is… how to get the cap off.

So you have a flat tire and want to try out Fix-a-Flat, a spray can that claims to seal and re-inflate your tire for temporary use until it can be repaired. Your first and biggest challenge is… how to get the cap off.

You squeeze and fiddle and twist and squeeze some more, with no success. You then go to the Internet and discover that this is such a common problem that the Fix-a-Flat website (but NOT the can) comes with instructions on how to get the cap off. They recommend wedging the can under a non-flat tire for leverage so you can wiggle the cap off.

“Sometimes our Fix-a-Flat caps suffer from separation anxiety and don’t want to come off.”

It turns out, this works. It would have been nicer if they’d designed a cap that could be removed with human hands, which seems like a well solved problem. But I guess if you ever encounter another kind of problematic cap, you could try this technique there!

1 Comments

1 of 1 people learned something from this entry.

January 1st, 2025 at 7:02 pm (Engineering, Spacecraft, Technology)

Recently I enjoyed working through Coursera’s Rocket Science for Everyone taught by Prof. Marla Geha.

The course reminds us that achieving orbit is all about going horizontally fast enough that you “miss” the Earth’s surface. For our planet’s mass, to achieve low Earth orbit, that speed is about 7.6 km/sec. I was interested to learn that given our available chemical propulsion options, we almost didn’t make it to orbit.

The rocket equation defines the change in velocity (delta_v) that you get from a given fuel and rocket design:

delta_v = v_exhaust ln(rocket mass [initial] / rocket without fuel mass [final] )

Exhaust velocity (v_exhaust) is how fast material is pushed out of the rocket, given the fuel you are using. This value for our propellants is about 2-3 km/sec, which means you need something greater than 95% fuel in order to get to 7.6 km/sec and achieve low Earth orbit! (By making that natural log of the mass ratio large enough)

Fortunately, smart people figured out that you can work around this limit using multiple stages and discarding spent containers to improve your mass ratio as you go. But if our planet had been more massive, we would have had to get a lot more creative to find something that would work.

Another bonus: launching near the equator and west to east gives you 0.5 km/sec for “free” (if you want an equatorial orbit). But Vandenberg Air Force Base (not equatorial) is a good launch site if you want a polar orbit instead (no freebies).

I also learned that GPS satellites are not out at geostationary orbit (which would allow them always to be in view, and only require three total to cover the Earth) because they didn’t want to have to build ground stations for them all over the Earth (i.e., in other countries) but instead just in the U.S. Interesting.

Great class – I recommend it!

Comments

September 6th, 2024 at 9:04 am (Engineering, Technology)

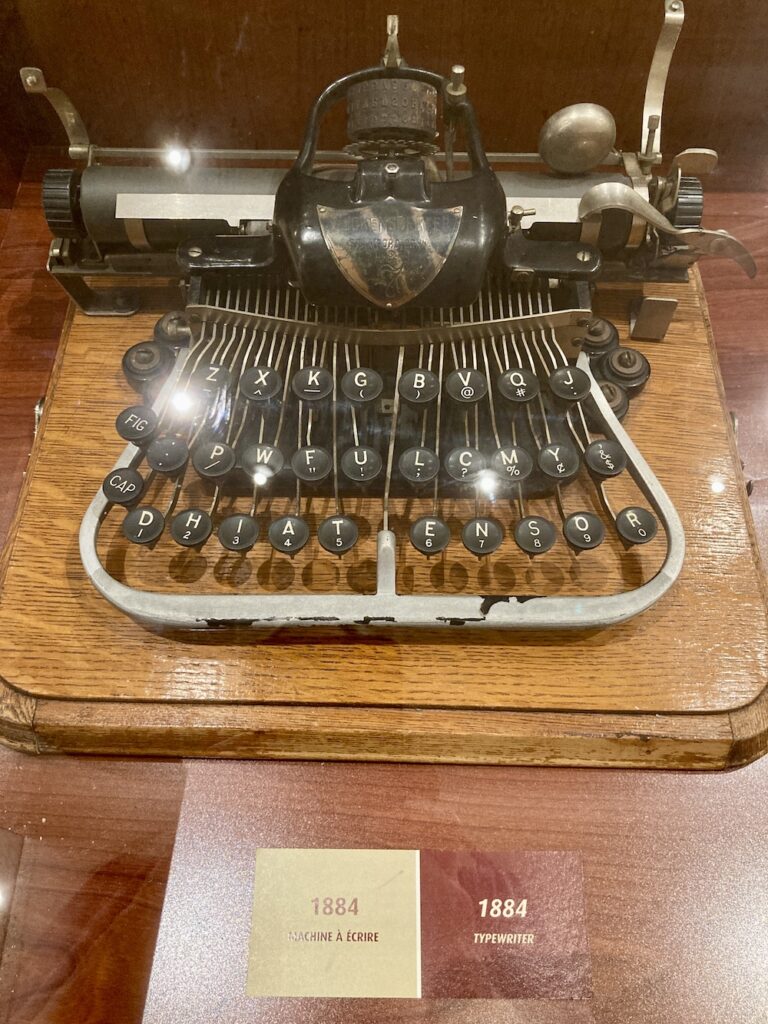

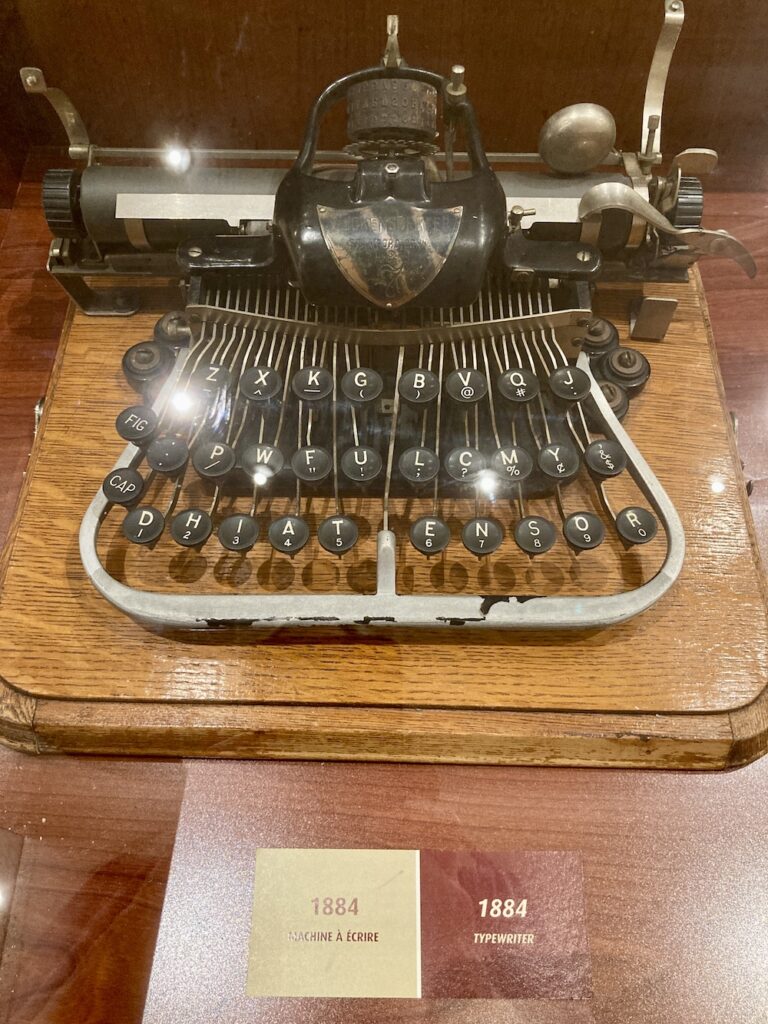

While visiting Montreal, I found this fascinating American typewriter on display at the small museum tucked into a grand Bank of Montreal building:

The compact size and unusual key layout caught my eye. I looked it up later and found out that it’s a Blickensderfer typewriter, invented in 1892 by George Canfield Blickensderfer. (Note that the caption says 1884 but I’m guessing this is a typo, since the Model 5 was not introduced until 1893, and the Model 7, which is what appears in the photo, was introduced in 1897.) It featured a lot of innovations compared to existing typewriters, including a much more compact size, fewer parts, lighter weight, the careful choice of keyboard layout, and a rotating typewheel that contained all of the letters and symbols in one place, in contrast to the individual key-arms with one letter per arm! The typewheel meant that you could change the machine’s entire font by swapping it for another typewheel.

The keyboard layout was carefully chosen. “Blickensderfer determined that 85% of words contained these letters, DHIATENSOR,” (Wikipedia) and so those letters were used for the home (bottom) row of the keyboard. The earlier QWERTY layout (1874) was designed to minimize the chance of the key-arms hitting each other, something the Blickensderfer model did not have to worry about.

I’d love to get to type on one of these machines. I’d have to re-learn touch typing with the different layout, but what a marvelous machine, packed with ingenuity!

Comments

July 13th, 2024 at 9:06 am (Finances, Technology)

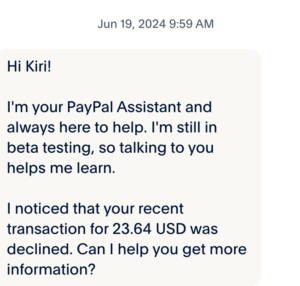

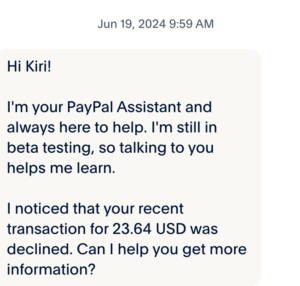

The other day, I couldn’t find some information I needed on the PayPal site, so I engaged with their generative AI chatbot. Before I could type anything, it launched in with this comment:

Hi Kiri!

I’m your PayPal Assistant and always here to help. I’m still in beta testing, so talking to you helps me learn.

I noticed that your recent transaction for 23.64 USD was declined. Can I help you get more information?

I replied “yes” and it gave me a generic link to reasons why a transaction could be declined. It refused to give me any information about the transaction it referred to.

I couldn’t find any such transaction in my account history. I therefore had to call a human on their customer service line to ask. Sure enough, they confirmed there was no such transaction. The chatbot simply made it up.

If I ran PayPal, I’d be terribly embarrassed – no one needs a financial service that generates red herrings like this – and I would turn the thing off until I could test and fix it. Given that this happened to me before I typed anything to the chatbot, you can bet it’s happening to others. If they were hoping the chatbot would save them on human salaries, all it did was create extra work for me and their customer service representative, who could have been helping solve a real problem, not one fabricated by their own chatbot.

I asked if there was somewhere to send the screenshot so they could troubleshoot it. I was told to email it to service@paypal.com . I got an auto-reply that said “Thanks for contacting PayPal. We’re sorry to inform you that this email address is no longer active.” Instead, it directed me to their help pages and to click “Message Us” which… you guessed it… opens a new dialog with the same chatbot.

This careless use of generative AI technology is a growing problem everywhere. A generative AI system is designed to _generate_ (i.e., make up) things. It employs randomness and abstraction to avoid simple regurgitation. This makes it great for writing poetry or brainstorming. But this means it is not (on its own) capable of looking up facts. It is quite clearly not the tool to use to describe, manage, or address financial services. Would you use a roulette wheel to balance your checkbook?

PayPal is exhibiting several problems here, all of which are correctable:

1. Lack of knowledge about AI technology strengths and limitations

2. Decision to deploy the AI technology despite not understanding it

3. Lack of testing of their AI product

4. No mechanism to receive reports of errors, limiting the ability to detect and correct problems

I hope to see future improvement. For now, this is a good cautionary tale for everyone rushing to integrate AI everywhere.

1 Comments

1 of 1 people learned something from this entry.

April 13th, 2024 at 10:38 am (Engineering, Technology, Travel)

It’s still early times, but what a captivating thought!

Last year, DARPA created the LunA-10 study, a 10-year effort that “aims to rapidly develop foundational technology concepts that move away from individual scientific efforts within isolated, self-sufficient systems, toward a series of shareable, scalable systems that interoperate.”

Last year, DARPA created the LunA-10 study, a 10-year effort that “aims to rapidly develop foundational technology concepts that move away from individual scientific efforts within isolated, self-sufficient systems, toward a series of shareable, scalable systems that interoperate.”

So far, our trips to the Moon have been isolated visits, but if we’d like to get serious about sustained activity, additional infrastructure (for mobility, communication, energy generation, etc.) would surely be useful.

Recently, Northrop Grumman provided some details about their part of LunA-10, which aims to develop a framework for a railroad network on the Moon. How cool is that? I’d love to be part of that study.

LunA-10 participant updates are planned to be shared at the Lunar Surface Innovation Consortium meeting, final reports from each of the LunA-10 participants will be due in June – here’s hoping they’re made publicly available.

Comments

So you have a flat tire and want to try out Fix-a-Flat, a spray can that claims to seal and re-inflate your tire for temporary use until it can be repaired. Your first and biggest challenge is… how to get the cap off.

So you have a flat tire and want to try out Fix-a-Flat, a spray can that claims to seal and re-inflate your tire for temporary use until it can be repaired. Your first and biggest challenge is… how to get the cap off.