How to drive a steam locomotive

July 16th, 2017 at 11:04 pm (Engineering, Technology)

I recently got to drive a steam locomotive! The Nevada Northern Railway in Ely, NV, allows you to Be the Engineer for a 14-mile trip up and down hills, through two tunnels, and across several road crossings. This is an incredible experience – visually and physically!

(By the way – I learned that you “run” or “operate” an engine, not “drive” it, since no steering is involved. But that is how they describe the experience to newcomers :) )

Did you ever see such a beautiful engine?

NN 40, built by Baldwin in 1910

Before climbing into the engineer’s seat, I had to study a 122-page rulebook and take a short (open book) exam. I learned about whistle signals, hand signals, speed limits, track warrants, air brakes, and more. I learned radio protocol (interestingly, it’s backwards from typical airplane conventions; you announce who you are and then who you want to speak with, e.g., “NN 93 to NN Conductor 93, over”). In addition, “the use of ten codes” (I assume this means things like “10-4”) is prohibited.

I also helped get the engine ready for action. The rest of the crew gave me small jobs, like greasing the many bolts that connect rods and other pieces, and refilling the oil reservoirs. Meanwhile, they stoked up the fire in the boiler, cleaned the engine, filled up the tender’s 6000-gallon water tank, and ensured we had enough coal. The steam engine goes through 75 gallons of water *per mile* and consumes about a ton of coal in the 14-mile trip we did!

After three hours of prep, the engine was ready to go! I climbed up into the cab and learned how to start and stop the engine, then practiced this while we were still in the railyard.

The primary controls are the throttle and the brake. The throttle is a squeeze lever with many (~20) detents. Bouncing along, it requires some fine eye-hand coordination to move it precisely to the desired notch. It, too, is backwards from the throttle on an airplane: moving it out (towards you) gives you more steam, not less!

The brake is a smaller handle, easier to manipulate. If you want to slow down, you move it to a setting that allows compressed air into the brake cylinders, pressing the brake shoes against the wheels. You monitor how much brake you are applying through a pressure gauge. Then you move the handle the other direction to release the compressed air (you can hear it hiss out) and the wheels resume unimpeded motion.

The massive locomotive responds slowly to control changes, so both controls are best applied with careful anticipation of the upcoming track – its grade, any curves, preparation for tunnels, etc.

There is also a reversing lever that is mounted vertically in the floor. As one of my books warns, “A strong arm is needed for the reversing lever!” It has a more subtle effect on locomotion by altering the amount of steam that gets into the piston cylinders on each stroke. You want it set full forward to get moving, then back it off for “cruise” to achieve more efficient operations.

And we were off! We left the railyard and climbed a gentle hill. We went through two tunnels and several road crossings. For each crossing, I blew the whistle – LONG LONG short LONG! Mike, our fireman, was busy shoveling coal as needed, injecting more water into the boiler, and ringing the bell through all crossings as well. What a delightful noise!

We used a GPS-based speedometer to track our speed, which stopped working each time we went into a tunnel. However, after a while you get a feel for speed based on the sound of the pistons (and such a lovely sound it is). Pistons mounted on each side provide the driving power for the large wheels. Each wheel gets driven twice per rotation (unlike engines in cars, airplanes, etc.):

In addition, the left and right wheels are offset in phase so that one side gets maximal torque when the other is at minimum (end of its stroke). So what you hear is CHUFF-chuff-chuff-chuff as the pistons go right-forward, left-forward, right-back, left-back, for a smooth continuous overall motion.

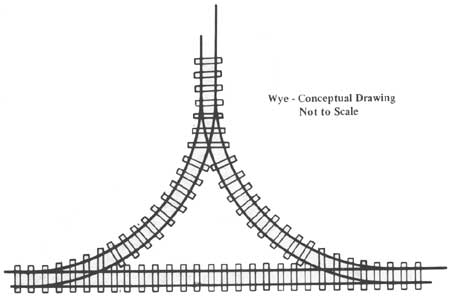

At the top of the hill, I gave the controls over to John, the engineer who was training me, and he traced our way through a “wye” (track set up to enable a three-point turn by an engine), which got us set up to return back downhill.

We then continued back down the hill to return to the railyard. The whole trip took about an hour and 15 minutes. After the initial learning curve, it got very comfortable to roll along and listen and respond to the chuff of the pistons as needed. My mind quieted and I filled up with the pure joy of the moment. What an overwhelming experience!

Me driving Number 40

Thank you to Richard Ondrovic for taking these fantastic photos!

What I Learned Today » Blog Archive » The Art of Getting There said,

July 30, 2017 at 7:06 pm

[…] Among other things, several of the pieces were inspired by the very steam locomotive that I got to operate a few weeks ago (see art at right!), as well as other engines and people from the Nevada Northern […]