Today our crew was interviewed by Amnon Govrin, a space enthusiast blogger. He brought his twin 9-year-old sons, and we had a good time showing all three of them around our Hab, GreenHab, Musk Observatory, and Engineering Station. Amnon came equipped with a sharp camera and a list of questions for us. The kids seemed really taken by anything vertical: the steps we climb up to our living quarters, the ladder to the storage loft, the hills outside the Hab, and so on. We had planned for an EVA to leave just as Amnon arrived, so he and his sons could see the whole suit-up and EVA preparation process.

I led EVA 19 off on a quest for Valles Marineris, accompanied by Mike and Darrel. In some ways, the Mars-y names assigned to these local Utah features feel a little weird. Our local Olympus Mons doesn’t rise much more than 65 meters above the surrounding plain, rather than the jaw-dropping 27,000 meters attained by the Olympus Mons on Mars (three times taller than Mount Everest). Likewise, our local Valles Marineris surely could not compare to the 7,000-meter deep feature on Mars. But I’d heard that it was still a sight to see, so I wanted to investigate first-hand.

This was a bit of challenge, since Valles Marineris is positioned on the same Cactus Road that we failed to find on EVA 16. The road had been washed out so badly that, with patchy snowcover littering the terrain, I couldn’t be confident that we were *on* a road. I am (maybe overly) cautious about exploring into the unknown because I really hate to cause any damage to the desert terrain, even aside from the BLM requirement that we stay on trails. But today we went out with fresh determination and scouted away from Lowell Highway until we found bona fide ATV tracks, just around a hill. Encouraged, we took off down “Cactus Road”, which was actually the muddy bottom of a trickling runoff creek. We came upon Valles Marineris almost immediately, as our creek-bed road cut down through 30-50 feet of layered rock. The mini-canyon walls rose up, revealing beautifully bedded layers. I was torn between stopping to photograph and inch along each bit of exposed section, and wanting to explore further with my EVA-mates. We’d only been out for about 15 minutes, and I knew we all wanted to go further than that! So we drove along further, eventually striking a road leading up a snowy slope to the south.We crested the hill and found ourselves on a wide plain. Truly deep canyons dropped off in the distance to our left (later we confirmed them as Candor Chasma, the subject of EVA 8). Closer in reach, a mountain with beautiful, striking bands of purple and red towered to our right. Squinting, I could even detect a tiny green layer sandwiched in. “That’s where we might find fossils,” I said, pointing. “That’s probably a green shale layer, deposited in a marine environment.” Darrel immediately jumped on this and proposed hiking up to the distant layer. I was a little leery of the steep, muddy slope, but it was just too tempting to pass up!

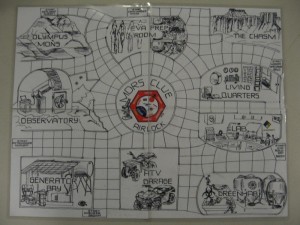

We scrambled and pawed our way up the flanks of the mountain (later identified as Mount Sagewood). At the top, we picked our way along the green layer’s exposure, conveniently at about hip-height. It topped a series of vivid red and purple bands, and the colors glowed in the noontime sun. We didn’t find any fossils… but may have found traces of endoliths, and the variety and beauty of the sedimentary structures was more than enough satisfaction for me. We then climbed the last 30 feet to the top of the mountain and enjoyed a beautiful panoramic view, with the Hab in the distance to the west, Olympus Mons and Factory Butte jutting up to the northwest, Valles Marineris dropping away to the north, and Candor Chasma floating like a heady mirage of sedimentary nirvana to the east. We oohed and ahhed and took tons of pictures, then carefully descended back down to the ATVs. Our trip back was quick, but very muddy. I waved Mike on to take the lead from Cactus Road home, and he clearly enjoyed racing through the muddy streambed, bouncing off rocks, and racing full-throttle back down Lowell Highway to the Hab.You can view the full EVA 19 information, including a map.

Amnon Govrin and his sons were just getting ready to leave, so Mike and Darrel ferried them back to Hanksville, and I helped Brian, Luis, and Carla get ready for EVA 20. Their intended destination was the pair of caves that had eluded Luis and Mike on EVA 15. They were equipped this time with a series of GPS waypoints that should have led them straight to Canton Cave. Unfortunately, they got all the way up near the cave, in Serenity Valley, only to find that the road plunged into a deep channel that could not be safely crossed with the ATVs. While they could have walked the last kilometer on foot, they were running out of time. They returned home, even muddier than we had been, disappointed not to have found the cave but still glad to have had one last EVA.

And here’s the full EVA 20 information, including a map.

It’s hit home with all of us that this has been the last day of our Mars mission simulation. Tomorrow will be filled with more cleaning, packing, and getting ready for the Hab handover to Crew 90. I realized that just recently our mode of operations here has really started to feel normal, and that I feel quite at home. Two weeks is just enough time to settle into a good routine, having smoothed out the rough edges. (It hasn’t hurt that Darrel has fixed or upgraded much of the Hab’s functionality during our tenure!) I expect it to be quite jarring to return to “Earth” life. I’ve certainly felt this to be a hugely educational, eye-opening, wonderful, beautiful experience. If what we’ve accomplished and learned can in any way translate into useful knowledge for a real human mission to Mars, I fervently hope that there will be a way for us to share.