After abdicating some tantalizing EVAs for the past three days on account of my not feeling well, I was looking forward to getting outside today and finally starting my seismic research project. I had originally planned to do the first seismic EVA yesterday, but I just wasn’t ready, so Kiri led the geology section EVA yesterday instead.

Darrel, Luis, and Brian in the airlock

My morning was occupied with preparations for the seismic experiment. This included finalizing the survey coordinates and entering waypoints into the GPS, printing and laminating a survey plan, and fashioning several survey flags out of wire clothes hangers and flagging tape. I also strapped the big, heavy pelican cases containing the seismic equipment to the back rack of the Viking I and Spirit rovers. I affixed the sledgehammer, strikeplate, and two bright red buckets to the third rover Opportunity. At 11:30 am, I briefed LuÃs and Darrel on the EVA plan. It clicked with Darrel right away, but LuÃs looked a little confused. We ate a quick lunch of leftovers from previous meals and were in the airlock at 1:07 pm.

Our difficulties began almost immediately upon our egress from the Hab. LuÃs and I hopped on the Viking I and Spirit rovers only to discover that our EVA suit backpacks stuck out too far for us to comfortably ride the vehicle with the boxes behind us. LuÃs decided he could manage since the box on his rover was positioned farther back than the one on my rover. We had to move the box from the back rack to the front rack on my rover, and this ate valuable time.

roving along

Twenty minutes later we finally rumbled off north from the Hab on the now familiar trail leading towards Olympus Mons. I led the caravan. With each dip and bump in the terrain, the box we had strapped to the front of my rover bounced. I had to keep a hand on it. Finally, just as we were turning west at the base of the hill crewmembers had climbed just two days ago, the bungee cords holding the box to my rover’s front rack gave way, and I barely caught it before it fell to the ground. I had to stop and put it back on the rover. LuÃs and Darrel helped. We moved it to the back rack where it originally was but were able to inch it back a little to give me enough room to sit down with the EVA suit.

On our ascent to the top of the ridge, we snapped a few photos and video footage. I had been here on EVA 13 just four days ago, and in that time the snow cover had thinned considerably. The dirt was even showing through in a few places. Another couple days of above freezing temperature, and the snow will be gone, replaced by the slippery muddy clay we experienced on our first two days at MDRS.

Darrel, LuÃs, and I enjoyed the expansive scenery of Mid Ridge Planitia as we motored south on along Radio Ridge under mostly sunny skies. I stopped at some of the same places where I’d taken geotagged photos on EVA 13 so Kiri could have overlapping shots for her auto-geolocation study. We arrived at the target location around 2:15 pm, a little over an hour after embarking on the EVA.

panorama overlooking Radio Ridge

I should back up and explain why I wanted to do the study in this location. Nominally, the main goal of the experiment is to test the feasibility of collecting a 2D seismic profile using a towed land streamer (more on what those terms mean later). However, if the exercise can be carried out somewhere with interesting geology, that’s icing on the cake. As luck would have it, MDRS Crew 83 led by Carol Stoker of NASA Ames collected ground penetrating radar (GPR) data earlier this field season data and discovered a buried feature where the Kissing Camel Range (aka: “Dragon’s Head”) intersects Radio Ridge. The interpretation is that Kissing Camel Range is an inverted channel that is covered by the Cretaceous sediments comprising Radio Ridge. An inverted channel is former streambed that filled with resistive material. Over time, erosion removed the surrounding surface leaving the former stream behind as positive relief (hence the “invereted” moniker). Inverted channels have been spotted in multiple locations on Mars, and one at Miyamoto Crater has been identified as a potential landing site for the Mars Science Laboratory.

Darrel and Luis discuss the survey strategy

Our first task was to survey the line for the experiment. Ideally, we’d have a theodolite or total station to make this work easier, but being resourceful Mars pioneers, we had to make do with the materials at hand. In this case, that meant a 50 meter tape measure, some homemade survey flags, a handheld GPS unit, and a compass. First, I walked the nominal 165 meter (540 ft) line I had planned for the profile and marked each end with a bright red bucket. Then, Darrel and LuÃs stretched out the measuring tape while I started unloading and hooking up the equipment. We had to adjust the the line a few times before I was satisfied it was straight. LuÃs put the survey flags at all of the planned shot points and spread endpoints, and Darrel marked GPS waypoints.

land streamer and astronaut shadows

Now we were ready to start the seismic survey. We pulled the land streamer out of its box and hooked it to the back of the Viking I rover. I drove the rover forward to extend the streamer. A land streamer is just a big cable with geophones attached to it that makes for relatively quick movement of geophone arrays. A geophone is the simplest form of seismometer. It converts ground movement into voltage that is collected in a seismograph, which is a rugged field computer for collecting seismic data. In our case, we have a string of twelve geophones spaced five feet apart. Since I’d spent the better part of three days playing with the geophones and seismograph back at MDRS, hooking it all up in the field wasn’t a problem. However, there was one big issue.

Brian with the dreaded laptop

The Geometrics Geode seismograph we have requires a computer to control it. If anyone has ever tried using a laptop outdoors, you know it’s difficult to see the screen in the sun. Now try that wearing a spacesuit helmet and using an old Panasonic Toughbook that is at least 10 years old (meaning its screen is quite primitive by today’s standards). All of these factors conspire to make seeing the one means of controlling the system nearly impossible. It took a while, but I was finally able to boot the computer and load the necessary software.

Luis swings the hammer.

We were finally ready to take our first shot. For those uninitiated in seismic exploration lingo, a “shot” refers to the source of seismic energy. It’s often an explosive source for large scale surveys, but for us a simple sledgehammer striking a metal plate will do. Darrel, LuÃs, and I took a few turns practicing our hammer swings before starting the data collection. Since radio interference could potentially corrupt the data collection, we turned off our radios and worked out a few hand signals to communicate. I squinted at the nearly black Toughbook screen while LuÃs took the first swing. The computer beep told me it successfully took a record of data, and LuÃs swung twice more so we could stack the data to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. Then, he picked up the plate and dropped it at the next flag. We repeated this for all six shot locations for the first spread location.

Then it was time to move the geophones 60 feet down the line and take more data. I drove the rover along while Darrel made sure the land streamer didn’t get tangled. I was impressed with how well the system performed and can appreciate why land streamers are very popular these days for enabling quicker more affordable seismic surveys. I had asked Darrel to tell via radio when I needed to stop, but I didn’t hear him. I overshot the mark and dragged the geophones too far. So, LuÃs and Darrel pulled on the land streamer while I backed up. This would have been fine except that I had drive over a big rock.

Going downhill over the rock meant the rover was tipped backwards pretty steeply. I had only loosely closed the box on the back of the ATV holding the equipment. When the rover pitched, the laptop slid out. In the process, it yanked the ethernet cable jack out of the PCMCIA card. Thankfully, the laptop itself escaped being run over by the vehicle, but the PCMCIA card didn’t fare so well. I shoved the ethernet jack back in hoping it would work, but it did not. The laptop started beeping, and it all three of us squinting at the black screen to get the computer rebooted.

to the Hab

It was clear that we couldn’t collect any more data with the computer until we fixed it, so we packed up and drove back. LuÃs led the way and took some amazing video footage along the way. When we returned, we were tired and hungry from the 4 hour, 19 minute EVA (our crew’s longest yet). Thankfully, today was a cooking day, and Carla and Kiri did not disappoint. They made baked tofu “cashew-dine” and vegetable couscous with apricot cinnamon biscuits and coconut brownies.

After a couple of hours wearing a headlamp and soldering tiny wires, Darrel was able to fix the Toughbook’s PCMCIA card. Kiri and I tried recovering the data from the laptop and to our horror found that it wasn’t there. According to the log files, the six shots we took today should have been recorded, but the data has vanished. Perhaps it’s related to the hard reboot we had to do in the field. Life on Mars is never easy. We’ll go back out tomorrow and start over. This time we’ll try putting the laptop in a cardboard box to reduce glare.

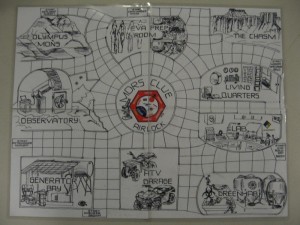

You can view the full EVA 17 information, including a map.

I’d like to thank Exploration Instruments, LLC for their generous loan of the seismic equipment for this study. Some day, astronauts on another world will need to conduct geophysical exploration of the shallow subsurface, and the work we’re doing helps identify how to modify terrestrial methods for extraterrestrial application.

I’d like to thank Exploration Instruments, LLC for their generous loan of the seismic equipment for this study. Some day, astronauts on another world will need to conduct geophysical exploration of the shallow subsurface, and the work we’re doing helps identify how to modify terrestrial methods for extraterrestrial application.